Coming from two films that are known for their intense visual extravaganza, I would like to turn it around a bit in this week’s Film Frame Friday with a touch of serenity. So sit back, relax, and let us watch Shinkai Makato’s picturesque scenes slip into the screen together.

A decidedly less depressing melodrama feature from Shinkai, the famed director of Byōsoku Go Senchimētoru (5 Centimeters per Second, 2007) and Koto no ha no Niwa (The Garden of Words, 2013), Kimi no Na Wa. (Your Name., 2016) looks at the collective experience of disasters at the individual level, highlighting the painful interaction of trauma with very medium-specific devices at his disposal. About a young boy (Taki) from the city and a young girl (Mitsuha) from the country inexplicably inhabiting each other’s body after a night’s sleep, this rom-com setup quickly turns into a traumatic experience when Taki discovers that Mitsuha is from the past and already dead, a victim of an asteroid crash on her hometown. Shinkai’s signature use of beautiful colors gives the sensational visual pleasure his films are often known for, but they also play a role in juxtaposing beauty with trauma: in this case, the asteroid disaster. Such a paradox forms the thematic backbone in the film’s visual and narrative foundation and guides the audience through the story of (fantastic) reclamation.

What interests me the most is the how that paradox is visually represented. The stark contrast between beauty (and the wondrous experiences associated with it) and trauma (and the painful experiences associated with it) are often side-by-side, as Shinkai highlights their differences as well as their connections. There is a binary, like any film with some sort of a rupture, but Kimi no Na Wa.’s binary is not necessarily irrevocable, but rather merely separated. Shinkai achieves this in a very animation-specific concept of “line.” The line in animation is the foundation of everything. We often refer to traditional 2D animation as 2D because it is made up of two-dimensional shapes, consisting of lines and colors. A line separates the inside from the outside, a character from the environment, clarity from obscurity. The line is the ultimate divider.

But that’s not always the case in the film. Just as the line divides, the line connects—another characteristic of a line. Horizontally, it separates but it also marks the edge where two objects meet, and vertically, it becomes a thread that ties two distanced objects together. The line also leads one from a place to another, as we often use the term to denote subway lines (in Japanese, subway lines are called Rosen, literally meaning “road line”). Metaphorically, a line becomes a line of clues that leads, in this case, Taki to Mitsuha’s past. These multiple meanings of line, often in terms of borders in live-action films, have been the thematic topic of many films, yet Shinkai’s work in this film is notable precisely because it is an animation. He is almost obsessively using the line in his visual direction. Here, the line separates, connects and ultimately leads the characters, trauma, memory and the story.

The most obvious way the director uses this is, of course, the concept of the red thread (akaiito), often connoting a fateful, romantic bond between a couple in East Asian culture, and a very overused cliché in Japanese anime. Here, the red ribbon connects Taki and Mitsuha, the past and the present, the couple, and becomes a leader to help Taki to avert the disaster. But it is not the only line featured in the film—in fact, a lot of lines in the film are often visual and metaphoric. The shot composition Shinkai frequently employs in the film is one that divides the screen with a line: like the reunion of Taki and Mitsuha on top of the mountain, a narrative point where the two finally meet face-to-face despite the temporal rupture that exists between them. It appropriately happens during twilight, the time marked by its in-betweenness, a line and a line-blurred. In this shot, Shinkai is fully aware of both the divisive and connective function of a line, using the paradox fully to his (and the characters’) advantage, reaffirming the separation between them while revealing the separation can be overcome. The line signifies where they are physically separate and where they meet spiritually.

Often, films (especially diaspora cinema) have used the concept of a border as the visual representation of social, cultural and political boundary. In anime, the most famous use of border comes in Neon Genesis Evangelion’s (Anno Hideaki, 1995-6) AT-fields, where border/boundary is conceptualized as the distinction between the self and the other. The crossing of that border was established by Tomino Yoshiyuki’s Mobile Suit Gundam (1979-80) and its concept of Newtypes, which proposes a utopian look at the abolishing physical boundaries.

Where Kimi no Na Wa. differentiates with both its live-action and animated predecessors is that it sees division as part of life, a fatalistic concept. Mitsuha’s grandmother, a Shinto priestess, teaches her granddaughters that the small stream on top of the mountain is the line between the world of the living and the world of death. The film does not necessarily see the dividing line (nor its necessity) as negative—instead, they are where two things are met and separated. Perhaps conceptually similar to Coco’s (Lee Unkrich, 2017) use of its own border, Kimi no Na Wa. realizes that lines form the basis of human interaction with each other, nature, and their own selves.

Take another example of a frequently used line in the film: the tail of the comet, which eventually crashes too (initially) unsuspecting Mitsuha’s small town, visually symbolizes the ultimate divide between Taki and Mitsuha. But it is also through the comet that numerous binaries are met: since the comet is the one that begins the story of the two, it connects Taki and Mitsuha, the living and the dead, the past and the present, the reality and the dream, the beauty and the trauma.

Of course, the comet itself is more of a “dot” than a “line.” The “dot” in the film represents the single largest catalyst between Taki and Mitsuha. But there is another “dot” in the film, or more specifically, in its title. The period ends a sentence, just as it ends a line. The film uses the “lines” to overcome the “dot” throughout, and while the “dot” arrives regardless, the humans persevere. Shinkai once said in an interview that this film is his own attempt to represent and cope with the trauma of the Tohoku Earthquake, and if understood in that perspective, it is not surprising the film’s fatalist look at nature is contained in a wholly humanist perspective. This is especially clear (with a hint of irony) in the shots of Mitsuha’s eye that hold the comet falling down.

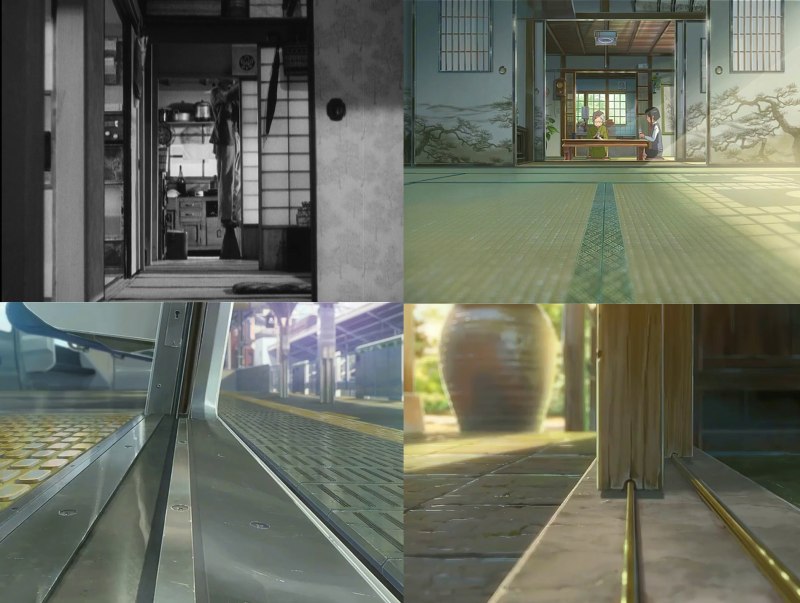

Coming back to the point of individual experiences of trauma as a frequent reminder to the audience, it is unsurprising then the concept of border is often unstable in the film. In a classic Ozu tradition, Shinkai repeatedly uses a shot of sliding doors (Mitsuha’s house to subway doors). Unlike Ozu however, who used sliding doors in deep-space compositions to reflect the flattening of 3D objects, Shinkai places the doors in the middle. This does not open the screen space to offscreen space and instead abolishes the divide within screen space. A typical hinged door prompts the subject to open the door to outside (pushing away) or the inside (pulling), which establishes individualistic subjects. Yet, the sliding doors, especially in the composition Shinkai gives us which places the doors as a line as opposed to a screen in Ozu’s frontal composition, do not have a single subject, and instead, operate to connect and divide the characters—a frequent visual significance that “lines” serve in the film.

The sliding doors either open/close intentionally (when Mitsuha opens her doors) or unintentionally (subway doors). The line that connects and divides us may or may not be up to our control, yet they are inherently permeable. The line separates yet connects-and this is why, coming back to the shot at the mountain where the two leads finally meet, all the dividers are at the same time connections. The film recognizes the destiny that arrives (comet, dot) yet it refuses to set the binary in stone, looking for ways to reconnect them. It is a human-centric drama that frequently searches for its own ending, it’s own “dot,” in the face of a seemingly inescapable traumatic destiny.

Maybe that is why when the title is said in the film, the dot, the period, isn’t there—it just hangs, for the audience. The line is there. It’s up to you to cross it.