About three-fourths of the way through Madeline’s Madeline, Josephine Decker’s explosive, performance-art-inspired new film, I found myself thinking one simple thought: “Actors are insane.”

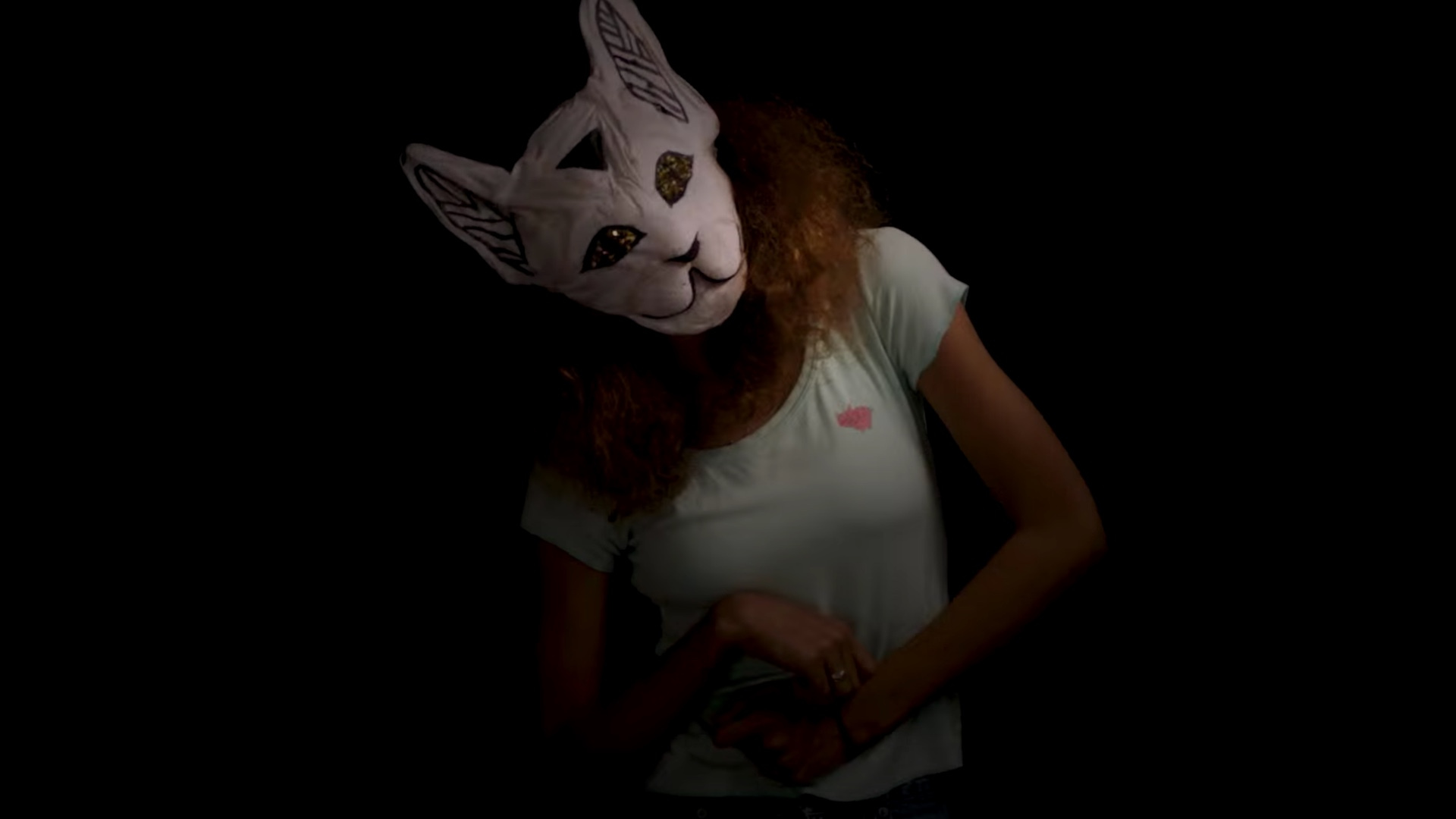

I believe it occurred to me during a sequence where the central character, Madeline (portrayed by a revelatory Helena Howard in her onscreen debut), bustles about the streets of New York City while donning a grotesquely shaped pig mask, huffing and snorting like the real porcine deal—but I can’t be sure, because the film is so chock full of delightful idiosyncrasies and performative flourishes that it’s downright dizzying. The act of inhabiting a character—not just playing someone (or something), but being someone—is a psychological venture of the highest degree, a blurring of mind and identity until no distinction can be made between performer and performance. Of course this is nothing new, actors have been turning in riveting work for decades, if not centuries (shout out to Gena Rowlands just because), but I have never seen a film articulate the frightening chameleonic depths of acting and collaboration quite like Madeline’s Madeline does.

That Madeline suffers from some form of mental illness (it’s never disclosed exactly what, but she takes medicine for it and has been hospitalized) only serves to heighten the tension. She is a sixteen year old girl living with her mother, Regina (Miranda July), and brother, Damon (Jaron Elijah Hopkins), dealing with all that that entails: hormones, mood swings, contentious relationships, what have you. With so much turbulence at home, she turns to her theatre troupe for reprieve, specifically her experimental instructor, Evangeline (Molly Parker), who is positively smitten with Madeline’s acting chops. A dual (or dueling as it were) mother dynamic begins to form, as Evangeline starts developing a play centered around Madeline’s life; at one point she even tells Madeline that she dreamt she was her daughter.

I could tell you more about the plot, but I’ll save that for another time because the film deserves to be experienced as freshly as possible. Still, without spoiling too much, I have to mention that the ending is an astonishing sequence of bravura filmmaking that is sure to make the synapses of even the most burnt out acidhead spark alive; there’s going places, and then there’s going places. The last ten minutes or so shoot for the stars, but the end result is something more akin to the big bang, the themes of performance and mental illness colliding and expanding in breathtaking grandeur, until we’re starkly brought back to reality with a final image that is, frankly, among the most devastating you’ll see all year.

What I can talk about though is the acting. Based on the title alone, it’s easy to surmise that this is Madeline’s show, and I can confidently say it would not be one tenth of the film it is without Howard’s magnetic presence. This is the type of performance that actors build their whole career towards; that this is her debut is beyond remarkable. She is asked to do so much, to be so much, bouncing through every emotion in the book and then some. Mental illness is often used as a crutch for actors, a green light to chew scenery and act in an obvious “dramatic” fashion. Howard doesn’t opt for that. Yes, she frequently displays a sense of wild energy, but it’s all in service to the wild energy of the movie, and she just as easily aces the quieter moments. This is a small film with a fairly limited release and is conveyed in a mode atypical of most movies. I don’t know what type of sway it’ll have come awards season, but if Howard doesn’t receive an Oscar nomination, I say lock up every member of the academy for criminal offences. She’s that good.

July and Parker are gems as well. I’ve loved Parker since Deadwood; she has a really calming voice and plays Evangeline with the perfect balance of warmth and distance. Her fondness for Madeline is apparent, but it’s almost always in service of her creative vision. July is appropriately spazzy as a worrisome theatre mom and delivers maybe my favorite line in the movie (I’m a sucker for anytime the word “spooky” is used).

A fair bit of warning though: if you don’t like experimental theatre and/or film, this might not be the movie for you. From the opening moments where Madeline pretends to be a cat—hairballs and all—to the film’s aforementioned virtuoso ending, Madeline’s Madeline is unapologetically weird. And not just weird in an offbeat humor type of way, ala the recent Sorry to Bother You, but in its frantic editing and distorted images. Cinematographer Ashley Connor has been mum on the specialized camera rig she used to shoot the movie, electing to preserve a sense of mystery, but the results are evident. Many shots feature a glossy veneer that emphasizes Madeline’s feelings of disassociation and imbue the film with a dreamy quality.

But if you can look past all that, or rather, accept it—it took me a bit to adjust to the frenetic style—you’ll find a haunting tale of a supremely talented teenager struggling with a haphazard mind. Madeline’s Madeline announces itself with gusto and certainly leaves a distinct first impression, but as time passes my appreciation for it only grows. Don’t miss this one.

One comment