Film Frame Friday is a regular series where one of our contributors will pick a film and highlight its unique cinematic style, from cinematography to mise-en-scene, and editing. It is a great way to not only introduce someone to a new film but to bring new conversations to the table. Click here for more entries in the series.

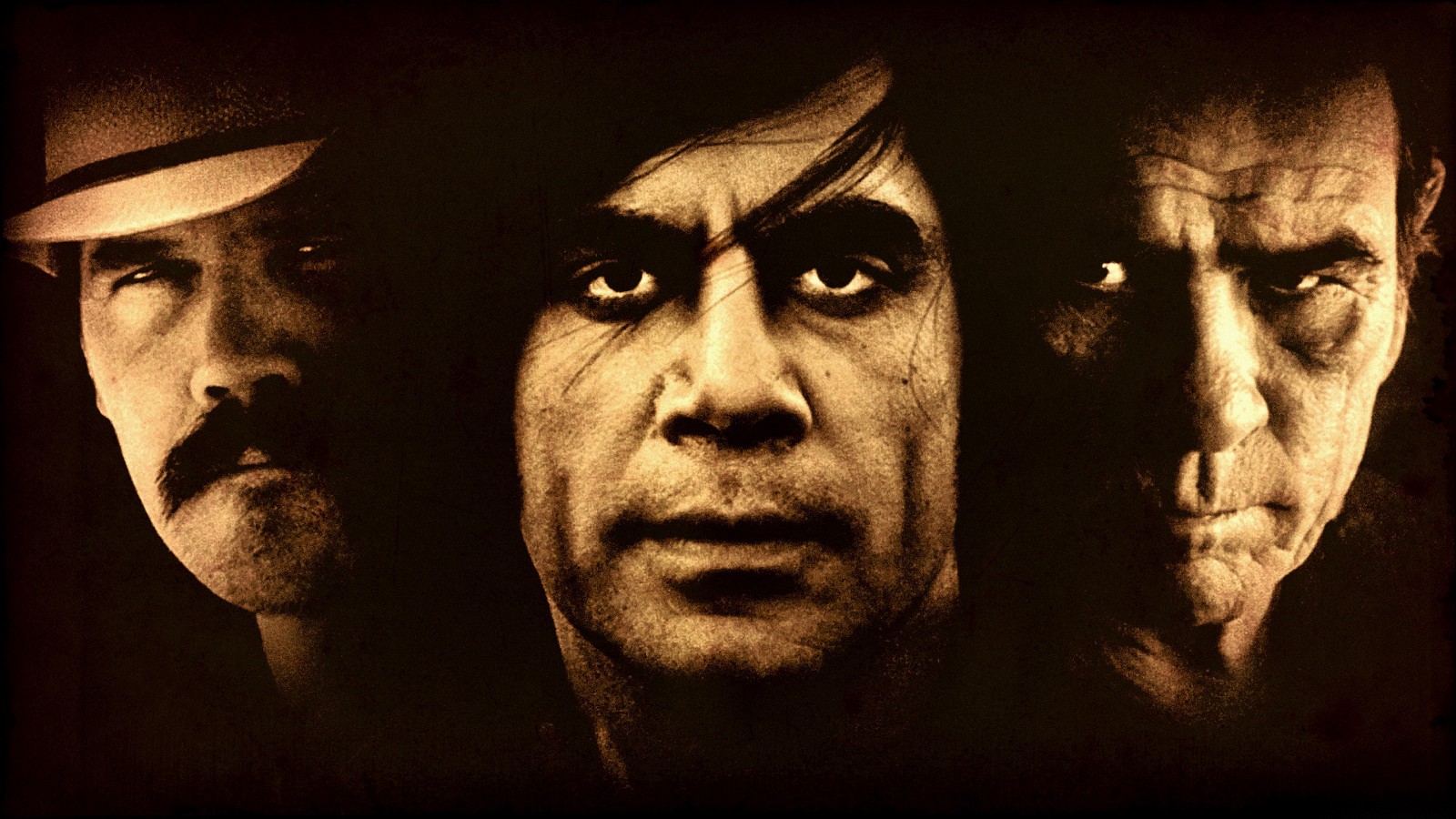

A Coen Brothers movie can be spotted a mile away. Look for noir elements, quirky characters, and human error; from such elements we get classics like Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and Burn After Reading. While these pieces play well together in a comedic tone, they can become dark and sinister with only a few small tweaks. There is no better example of this than the 2007 neo-western No Country for Old Men.

The film is an adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s book of the same name. Both works are harrowing modernizations of the Western genre. There are no lone rangers or valiant victories. It’s a world of poverty, psychopaths, death, and hopelessness. The law doesn’t win. The good guy doesn’t win. The bad guy doesn’t really win either. And it all just happens on screen in objective, nihilistic fashion. I respect the Coen Brothers; they could’ve easily played all of this for laughs, but they were true to the book and its intention, and they built the film around that existentialist intent.

Being nihilistic in nature, the Coen Brothers use voids and emptiness when constructing the cinematic experience of the film. This is particularly apparent in the sound design. The film has little to no score. Or dialogue. Or anything. There are portions of this film that are just long stretches of silence. The only sounds heard are those that are diegetic and absolutely necessary to tell the story. It’s a matter-of-fact approach that compliments this story of “man versus inevitability” quite well. In a traditional film, sound design suggests other parts of the world that aren’t in frame. For example, if the scene is a commander walking across a military base, then you would not only hear the commander, but also basic training, practice ranges, rhythmic call and responses, aircraft landing or leaving, and much more to add to the size of the operation without the need of showing it. The only things you hear from off screen in No Country is either existential narration from Tommy Lee Jones or the incoming threat of Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem). The complete lack of sound in this film suggests a void that the main character Llewelyn (Josh Brolin) is wandering in. The startling silence is incredibly effective, giving those quiet moments an ominous presence while giving the louder shootouts so much greater impact.

The cinematography plays with these voids just as much as the sound design does. Darkness is often used in the film to frame characters or vice verse with backgrounds silhouetting characters. Both techniques bring to mind the darkness motif again. Within the frames themselves, the use of emptiness is emphasized by a lack of periphery details. Every character who appears on screen has lines. There are no extras or CGI crowds, just a bunch of people directly or indirectly involved in Chigurh’s hunt for Llewelyn. In nihilism and other fate-oriented philosophies, one main similarity is that, in the face of death, every one is the same, no matter their status or earthly wealth. The silhouettes and darkness have this effect. Everyone looks the same in the dark. The only person you can distinctly recognize in silhouette is Chigurh, which says something about him as a figurehead for chaos.

Chigurh is an archetype found often in many post-modern stories that I will just dub “The Comedian”. The basis of the Comedian character is that he realizes the reality of his existence, processes it, and continues living by “laughing it off” or accepting the chaos wholeheartedly. You can see this archetype in the Dark Knight’s Joker, Watchmen’s Comedian, or even Sisyphus in Camus’ existential manifesto “The Myth of Sisyphus”. With this archetype being the foundation, how Chigurh is designed and captured on film adds layers to the film’s message.

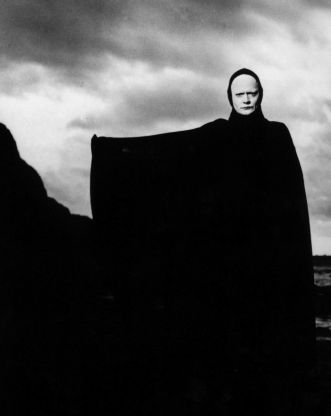

For one, his look is so distinctive. The world of No Country is full of jeans, boots, belt buckles, button ups, and leather. The men are all wearing their hair close to their head, and the women all have manicured nails, roughed up by being in the country, and hair that they take an awful lot of pride in. And then we have Chigurh. His dark palette goes against literally everyone else, an obvious example of how he is aesthetically different. His gait, his accent, his weapon of choice, his conversation… all make a prime example of a sore thumb. The haircut is just the icing on the cake. The strange length and cut of it are so un-American or fashionable and, as I mentioned before, make his presence strange but recognizable. It reminds me of Death in The Seventh Seal, and the relation between the two characters is obvious.

Given the film’s theme of man versus inevitability, and Chigurh’s role in that theme as the bringer of the ultimate inevitability, the Coen Brothers often frame him as such, focusing on his dark visage or—in the case of one shot—the symbol of finality at the end of a passage. The editing also sees Chigurh’s deeds as meaningless. Often times deaths will happen swiftly and with grotesque realism or, perhaps even more telling, not shown at all. Main characters die completely off screen. No pomp and circumstance, no swan song. Just dead. The realism is as matter-of-fact as the rest of the filmmaking. It’s not there to shock, it is there because that is what happens in the story. The Coens give the audience a completely grounded world. What is so disturbing about the film is how emotionally realistic it is. Whenever people die in the real world there is often no large set piece for a blaze of glory. The top billing dies like the day players. And towards the end, it rings true that even the worst among us can get hurt in this chaotic and messed up world.

No Country for Old Men is an existentialist Western examining the anxieties of mortality. It is a benchmark in post-modern filmmaking. It draws on older genres and stories but captures them with such a bleak and hopeless perspective, the absurdist nature of the world can be nowhere else but in the forefront of the audience’s mind.