Legacy is a tricky thing. As a species, we have a tendency towards propping up certain narratives and ideas as definitive, but the totality of life defies such narrow constrictions. It’s nice to think that the essence of a person can be summed up in a few anecdotes, or perhaps a biography if the subject is worthy enough, but the fact is, most people are many different things over the course of a life; as the great Walt Whitman eloquently put it, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” In this regard, celebrities arguably have it worse than anyone, being the only people on the planet whose lives are dissected on such a grand scale. We see them on screen and in the public spotlight, read interviews and tabloid pieces, and naïvely believe we know them, or at least know enough. But more often than not we are privy to a fraction of the truth, if that.

Just ask Robert Clift. Growing up, he was regaled with countless stories about his uncle Monty—better known to the public as the dreamy, immensely talented thespian Montgomery Clift—stories that painted him in a far different light than the commonly accepted narrative that he participated in “the longest suicide in Hollywood history.” Yes, he had his share of demons and a substance abuse problem that ultimately led to his untimely death at just forty-five years of age, but his life was not defined by tragedy. As Robert’s new documentary Making Montgomery Clift proves, Monty was a jovial man with a great appreciation for the pleasures of life, a jokester, a lover, and a revolutionary cinematic figure all wrapped up in one. Tired of the misconceptions and falsities, he, along with his wife and co-director/editor Hillary Demmon, have created an insightful tool to help combat the court of public opinion.

It’s worth noting that Robert was not the first member of his family to mount an opposition against Monty’s legacy; his father, Brooks Clift, harbored a borderline unhealthy fascination with how his brother was remembered after his death (and to be fair, how could he not when his image was constantly disparaged). Brooks served as an intelligence officer in World War II, and because of that he developed a tendency to record everything. And I mean everything—at one point Robert astoundingly mentions discovering a taping of a conversation that he and his brothers had about porn during their adolescence. Naturally, this trove of archival audio plays a big role in the film, offering direct accounts of his phone calls with Monty and biographer Patricia Bosworth, whose 1978 biography arguably shaped Monty’s narrative more than anyone else. She is also interviewed in the film, along with his good friend and former lover Judy Balaban, and the now deceased Jack Larson (another former lover and Jimmy Olsen in Adventures of Superman) and Lorenzo James, who lived with Monty at the time of his death and declined to appear on camera. James’ contributions are particularly affecting, his voice conveying a deep sense of love and admiration (Robert refers to James as his “uncle by way of Monty”).

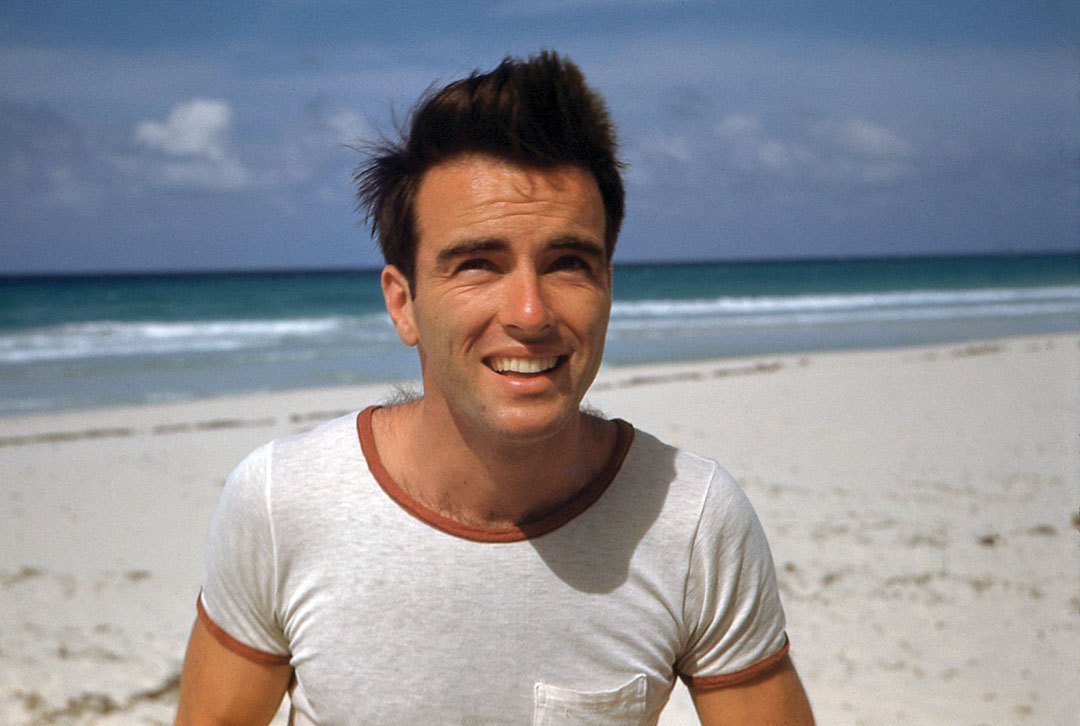

For those unfamiliar, the film starts off by detailing who Monty was, removed from any sort of bias. A maverick stage actor, and a damn handsome man, he made his screen debut in 1948 with a pair of films: The Search, which earned him the first of four Academy Award nominations, and Red River, starring opposite of the “Duke” himself, John Wayne. His arrival, along with contemporaries like Marlon Brando and James Dean, signaled a new era of naturalistic acting and a defiance of the type of masculinity typically portrayed at the time. Monty proved that male actors didn’t need to adhere to such stringent and emotionless characters: a perfect foil to Wayne’s classic machismo. He was so talented, at first he even refused to sign a major studio contract, the norm at the time, knowing full well they wouldn’t be able to resist his star power. At one point he turned down fourteen roles in one year, much to the chagrin of his agent. And when he finally did sign, he used his clout to leverage a level of creative control practically unheard of at the time, guaranteeing him the right to rewrite any line of his in a manner he saw fit. One of the coolest parts of the movie is seeing the actual script notes and changes he made overlaid on famous scenes of his. He frequently cut chunks of dialogue out, usually for the best. In his mind, less was more.

Monty was also bisexual, a fact that biographers and tabloids would have you believe was the source of his troubles. The story goes that his repressed sexuality and the affiliated shame of living a double life was too much for him to handle. Not so, says his closest friends. James emphatically denies that Monty was closeted, and Larson reveals it was Monty who made the first move in their relationship. No, the true (or at least most widely accepted) cause were the injuries he suffered during a car accident in 1956, all mostly to his face. He was not vain about it—he actually preferred not being so handsome and all his favorite performances were post injury—but the pain did lead to him abusing painkillers and alcohol.

Making Montgomery Clift is an obvious labor of love; not only is it a much needed reassessment of a classic Hollywood icon, it’s clear from the jump the effect Monty’s legacy had on his family. While it’s not exactly an examination of transgenerational trauma, Robert’s narration certainly hints at a shadow that had lingered over him, which he perhaps inherited from his father. The use of unique archival material allows for a level of intimacy rarely seen in biographical documentaries of this sort, and the way Demmon pieces everything together—the audio, the old movie footage, the interviews, the newspaper clippings, etc.—is impressive, as the film flows seamlessly from topic to topic. Of course presenting a definitive summation of a life is an impossible task, and the two never attempt to do so; instead, the goal was to simply broaden the picture and reveal inklings of truth that had been obscured or misrepresented over time. With that in mind, mission accomplished.