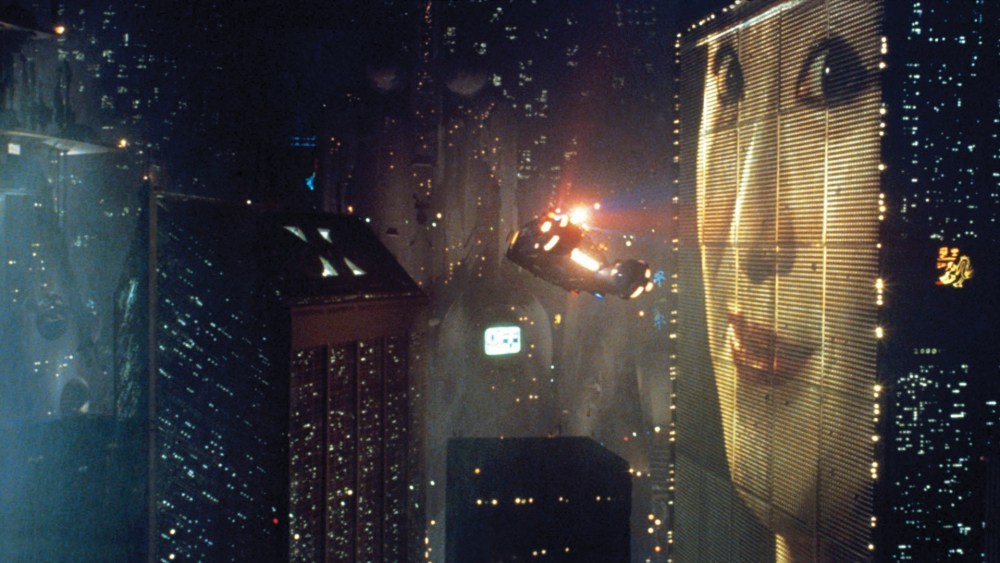

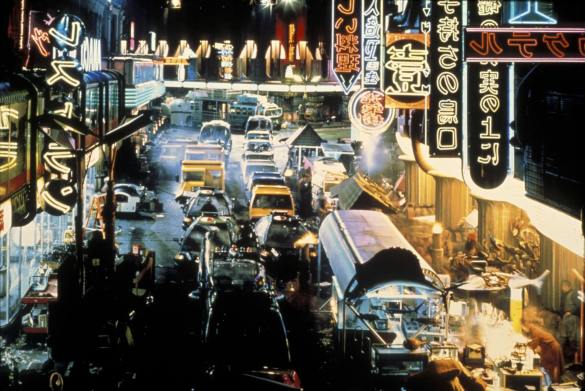

We’re living in the future. Or at least what was once the future; there was a point even in recent history when the year 2019 seemed far away. Ridley Scott’s science-fiction classic Blade Runner (1982), Katsuhiro Otomo’s animated cyberpunk Akira (1988), and The Spierig Brothers’ vampire horror Daybreakers (2009) all use our present year as the backdrop for their dystopias. Blade Runner is set in Los Angeles, transformed by thick rain and smog and a blend of foreign influences. Los Angeles is a sea of neon, advertisements, and machinery aglow against the gray decay of the environment. At the start of Akira, a nuclear blast destroys much of Tokyo, and the 2019 crime-ridden version of the city is called “Neo-Tokyo,” while after a mysterious outbreak, vampires make up 95% of the population in Daybreakers and create a dire shortage of blood. These 2019 landscapes are dirty and decaying, corrupt and on the verge of collapse, but still not entirely unrecognizable to contemporary audiences.

If there’s one thing that these projections of 2019 and our actual 2019 have in common, it’s that mega-corporations seem to dominate the world. In Blade Runner, skyscrapers are emblazoned with enormous glowing advertisements. Sophisticated androids known as “replicants” are created by a company called the Tyrell Corporation, which uses the beings that are virtually identical to humans as slave labor in their colonization of other planets. The replicants who have come to Earth illegally now face the threat of extermination, as they are hunted by former police officer Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), who must identify them (using the help of a “Voigt-Kampff” test) and kill them. But as the replicants are designed to mimic humans and their emotions in every way, and even have false memories implanted, it becomes practically impossible to tell the replicants from the humans except for their shimmering eyes. The moral struggle of determining who is allowed to stay in this country, or on this planet, has contemporary resonance—and even if the replicants were created by Tyrell to be “more human than human,” that rhetoric is ignored whenever it is convenient or profitable.

Daybreaker’s vampires are not being hunted: they are the privileged population. Whereas vampire Edward Dalton (Ethan Hawke) searches for a cure, Charles Bromley (Sam Neill), the blood- and power-thirsty owner of a blood supplier corporation, wants to spend his eternity being as rich as possible, preferring to monopolize the market and exploit the precious resource of human blood than to switch to the viable renewable resource of artificial blood. Perhaps the most pressing question these films raise is not just the broader existential one of What does it mean to be human, but instead, How do we determine who is deserving of human rights? People, replicants, vampires: these are all beings being exploited and deprived of agency in order to be turned into labor or food, or make a profit, discarded or “retired” when they are no longer of use. Corporations are the monsters and machines, and everyone else is the products they are selling.

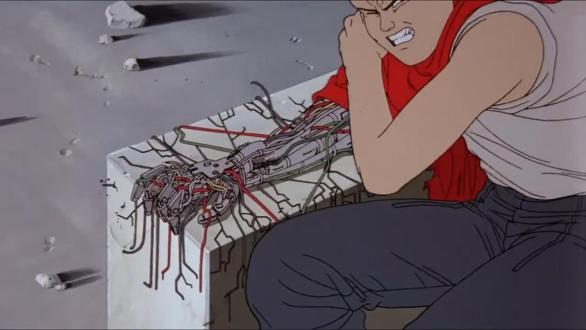

Meanwhile, Akira’s Tetsuo (voiced by Nozomu Sasaki) and his motorcycle gang, the Capsules, face off against their rival, the Clowns, amidst a series of large anti-government protests and terrorist threats. A crash with an esper named Takashi unleashes psychic powers in Tetsuo, and he suddenly garners the attention of “the Akira Project,” a secret government experiment to imbue subjects with telekinesis. The mass riots in the streets of Neo-Tokyo reveal the ineffectiveness of the government in serving the people’s needs, and Tetsuo too eventually breaks out of the government lab, perhaps a symbol of the youth trying to gain control over their own powers and overcome their societal alienation. Tetsuo is an angsty teenage boy dealing with all the typical crises of adolescence even without the added psychokinetic powers, which turn him into an unpredictable ball of masculine energy. The oppressive political forces are constantly trying to undermine the individual’s control over themselves, to seize control over the dominant narrative, to make Tetsuo doubt his own potential to create entirely new universes and render the powers that be obsolete.

2019 in these works is somewhere between the end of the world and the beginning of a new one. Technology is retrofitted, supplementing the old systems, and there is almost a complete environmental annihilation as nature starts to rot. Animals are noticeably absent, and displaced people struggle to survive while the empty shells of humans in power continue to exploit available resources. The constant presence of neon lights and vibrant colors take the place of diverse wildlife, the dazzle of the flying cars or motorcycles with glowing trails distracting from some of the grime and poverty. Even though it may feel as if we are living in some sort of dystopia now, in a 2019 of increasingly sophisticated and human-like technology, of immense corporations, of distrust in the government, and of the threat of nuclear weapons or impending environmental catastrophes, there are still hints of hope for the future in the bittersweet endings of these films. Blade Runner has multiple different endings, depending on which cut you watch, but we see Deckard leave with replicant Rachael (Sean Young), and he might even be a replicant himself; it seems promising that Dalton’s vampire cure could be used to save humans; Tetsuo triggers a big bang to create his own universe. As for this timeline of 2019, we will just have to wait and see what developments our own future brings.

To help us continue to create content, please consider supporting us on Patreon.