Agnes? It’s me, Billy…

Despite its dread effectiveness, Bob Clark’s 1974 holiday slasher Black Christmas has a legacy that feels more like a footnote than anything; it’s celebrated more for its influence on more successful films to follow than its own virtues. John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978), for example, would earn the lion’s share of credit for kickstarting the slasher boom of the 80’s (which is hard to argue given its widespread success), but it owes an obvious debt to many aspects of Black Christmas, from the anonymity of its evil stalker, to the voyeuristic point of view shots. Clark even claimed it spawned from a conversation he had with Carpenter about making a sequel to Black Christmas called Halloween. But Black Christmas deserves more than a footnote, and referencing it solely in relation to the films that have been built on its shoulders is to do it a disservice; it’s a terror worth celebrating all on its own.In general, horror films tend to fall into one of two categories: those where the characters enter a world of darkness and suffering that’s wholly other from their own, and those where the darkness and suffering enter the world of the characters. The films that fall in the latter category tend to be the most effective for me, because of their intrinsic relatability. We can choose not to venture into the dark unknown of a dark castle perched high on the hill, or the abandoned insane asylum, but we have no say in whether our homes get invaded. Black Christmas belongs to the latter category, as a manic stalker invades a sorority house during the Christmas holiday break. The film maximizes its terror not just by making its particular brand of darkness and suffering uniquely scary, but by making the world of its characters as cozy, inviting, and, crucially, familiar as possible. After all, what’s more nostalgic than the warmth of a decorated house keeping the cold of the winter season at bay? It’s in the crooked, perverse space between the contrast of fear and comfort that Black Christmas, the unsung progenitor of legions of celluloid slaughters and screams, truly chills.

Black Christmas, which Clark made nearly a decade earlier than his holiday hit A Christmas Story, is imbued with the same cheery attention to detail that made the latter film so popular during the season. Black Christmas was shot with a very grain-heavy film stock that gives the picture a soft, gauzy look, all the better to accentuate the glow of Christmas lights, burning hearths, and flickering candles that supply the light sources, and to bring out the saturated reds and yellows that the sorority house is decked out in. If someone came into this movie at the right time, without further context, they could easily mistake it for a genuine holiday romp, as all sorts of colorful and humorous characters bounce off one another in the splendidly detailed setting that we come to know so intimately. Of course, showing off the house so much with Clark’s highly mobile camera isn’t just to let us warm our toes in the cheerful mise-en-scène, but to establish the geography of the house where all of the suspense unfolds.

Black Christmas, unlike many of the slashers to follow, has a largely female cast that feels like a group of actual characters rather than bodies to be used for audience’s leering eyes and the killers’ weapons of choice. There is no gratuitous nudity here, and even the death scenes are more painful in their implication than in any explicitly rendered violence. Jess (Olivia Hussey as the de facto protagonist) has her own set of aspirations that go beyond both the boundaries of the picture or the desires of her domineering (and psychotic) boyfriend Peter; it’s revealed she is pregnant with his child, but rather than giving up her dreams to settle for motherhood with a child she doesn’t want and a man she doesn’t want to be married to, she calmly explains to Peter she wants to get an abortion. The movie casts no judgments on Jess for asserting her own agency and independence (indeed it’s even seen in a heroic light when taken with her determination to risk her life to save her friends later in the film), just as it doesn’t portray the other young women’s command of their sexuality, or crude humor, as somehow lesser traits for a woman to have. There is no conservative moralizing here; the sorority house feels populated by realized people. Even Margot Kidder’s character Barb, the foul-mouthed and likely alcoholic leader of the girls, is portrayed with human depth rather than the crude stereotype we see in slasher films down the line. There’s a real sense of pathos from the implied parental absenteeism that marks the trauma behind her bad behavior, and the rest of the girls all come together to support her and opt to spend their winter breaks with her. The only girl who doesn’t take up Barb’s offer is Claire, who is going back to her own family and thus earns Barb’s scorn as a reflection of her pain. Claire too, the ostensible “good girl“, would become a stereotype in later slashers as a the pure “final girl”. But in Black Christmas, even the good girl has lewd posters adorning her walls and is the first to die, not the last to survive as she might have in a later slasher. When taken with the yuletide atmosphere and the many humorous touches (including a particularly funny extended gag involving the word “fellatio” and a rather ineffectual policeman), Black Christmas accomplishes what few slashers since have managed: you actually feel really bad when these characters start to be murdered, because there is a warmth of human spirit to contrast the ice cold killings.

With such a well-established sense of comfort in atmosphere and intimacy in character, it’s natural that any disruption will feel that much more invasive and perverse. Unlike many horror films that build up to both the audience and characters becoming aware of the emerging danger, Black Christmas sets at least the audience up right away, by showing—through a disorienting wide-angle POV shot—an obviously mad intruder climbing up into the attic of the sorority house. By giving us this crucial bit of information upfront, the suspense of knowing the killer is lurking upstairs the entire time hangs over the rest of the film. When the girls start to receive disturbing phone calls from the killer, Billy, they are unsettled but have no reason to believe they’re in imminent danger. After all, they’re locked up in their cozy little house with all their friends, so what could go wrong? But we know better. And just who is Billy, exactly? Part of the terrifying brilliance of the film is that we never learn exactly who this anonymous threat is—he represents a terrifying vacuum to counter the well-sketched protagonists. Rather than divulging his backstory in an expository dump like many other horror films might do, the only information about Billy we can glean has to be parsed through his lunatic ravings and menacing phone calls. If you listen carefully you’ll come to learn that Billy may have done something very bad to his baby sister Agnes when he was younger, as his vocal inflections mimic what we assume are his parents asking what he’s done to the baby. Later he ominously intones: “Don’t tell them what we did, Agnes.” The brevity and obliqueness of the killer’s story allows the audience’s imagination to run wild and fill up with all sorts of tenebrous thoughts.

Billy’s unhinged ramblings and phone calls are upsetting even to this day. His voice is largely provided by actor Nick Mancuso; however, they used additional voices (even Bob Clark provided a few shouts and grunts) and recording processes to obfuscate his identity and provide the eerie schizophrenic rantings he has between several of his “characters”. However, the scariest moment of his phone calls comes from when he drops his bizarre vocal inflections and tells Jess in a voice that’s perfectly calm and eerily sane: “I’m going to kill you.” Billy’s matter-of-fact tone makes the line all the more unsettling; he is aware of what he’s doing, and we believe him.

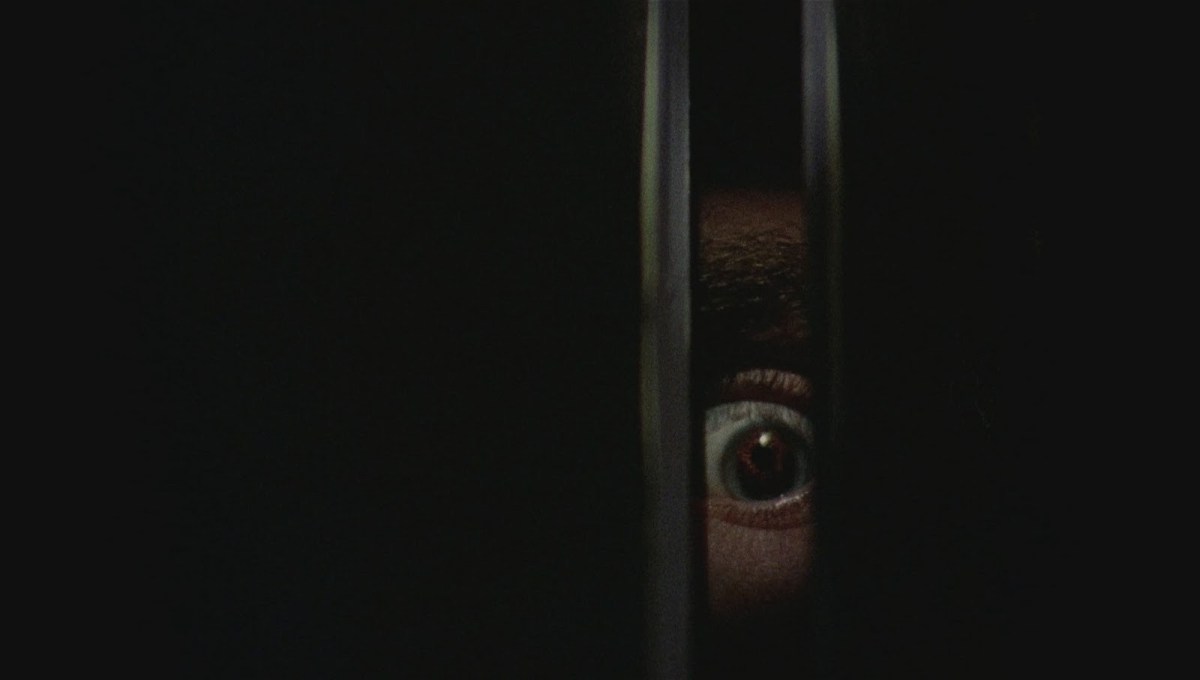

The film’s smartest, and scariest, trick is in its third-act bait-and-switch. We never see more than glimpses of Billy throughout the film: his absolutely unhinged eye peering through a doorway, the arm of his green sweater, and at most the shadowy visage revealing a shock of unkempt hair. Because Black Christmas is widely considered the first slasher film (although some credit Mario Bava’s body-count giallo A Bay of Blood (1971), or even Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960)), audiences at this point were accustomed to knowing the identity of killers. If a film withheld the knowledge of its hidden killer, that simply meant the movie was a whodunit, in which viewers would scour the picture for clues leading up to the eventual reveal. Black Christmas plays along with this expectation and cannily plants all sorts of clues, until the evidence seems positively overwhelming that Jess’s unstable boyfriend Peter is the killer. He is potentially insane: we see him demolish his piano after a recital doesn’t go as he planned. He has the motive: he is furious that Jess wants to have an abortion and refuses to marry him. He fits the description: his hair and attire certainly look like they could match up with what little we’ve seen of Billy, and we know the killer is adept at changing his voice. By the time the chilling climax occurs, in which Peter breaks into the sorority house and corners Jess before she kills him in an act of assumed self-defense, we are able to breathe a sigh of relief. Only, it turns out Peter was the wrong man. Sure, he was an unhinged creep and yet another patriarchal figure trying to control the women of the picture, but he wasn’t our killer (and if you watch the movie carefully, you’ll notice the shadow of the killer lurking around the house at times when it couldn’t possibly have been Peter).

The film leaves us with what can only be described as insurmountable dread. Billy remains unknowable, inexplicable, and undetected; and Jess, the hero whom we come to care so much about as the film’s great beacon of strength and independence, is helpless and undefended from whatever horrors we imagine Billy has in store for her. The film closes with a protracted wide shot of the sorority house as the credits roll. A police officer is left to guard the front door, ignorant to the monster still lurking in the attic, and the phone begins to ring once again. The ringing grows louder and louder in a mounting siren song of unspeakable evil. The glow of the house illuminated by Christmas lights is an image of perfect serenity, but the ringing of the phone creates one last noxious contrast between fond memories and insoluble nightmares. Christmas carols and screams, snowflakes and blood, a peaceful façade and the killer within—these are the horrifying battlegrounds that truly cement the unholy legacy of Black Christmas.